Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, and therefore they could not enjoy the rights and privileges the Constitution conferred upon American citizens. The decision is widely considered the worst in the Supreme Court's history, being widely denounced for its overt racism, judicial activism, poor legal reasoning, and crucial role in the start of the American Civil War four years later. Legal scholar Bernard Schwartz said that it "stands first in any list of the worst Supreme Court decisions". A future chief justice, Charles Evans Hughes, called it the Court's "greatest self-inflicted wound".

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision ruling that the freedom of speech protections in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution restrict the ability of public officials to sue for defamation. The decision held that if a plaintiff in a defamation lawsuit is a public official or candidate for public office, then not only must they prove the normal elements of defamation—publication of a false defamatory statement to a third party—they must also prove that the statement was made with "actual malice", meaning the defendant either knew the statement was false or recklessly disregarded whether it might be false. New York Times Co. v. Sullivan is frequently ranked as one of the greatest Supreme Court decisions of the modern era.

In United States constitutional law, incorporation is the doctrine by which portions of the Bill of Rights have been made applicable to the states. When the Bill of Rights was ratified, the courts held that its protections extended only to the actions of the federal government and that the Bill of Rights did not place limitations on the authority of the state and local governments. However, the post–Civil War era, beginning in 1865 with the Thirteenth Amendment, which declared the abolition of slavery, gave rise to the incorporation of other amendments, applying more rights to the states and people over time. Gradually, various portions of the Bill of Rights have been held to be applicable to state and local governments by incorporation via the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of 1868.

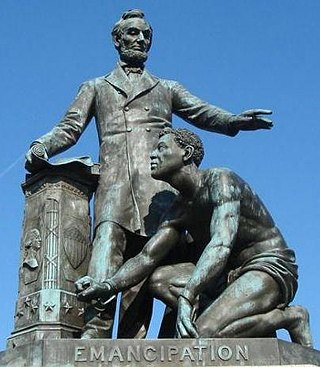

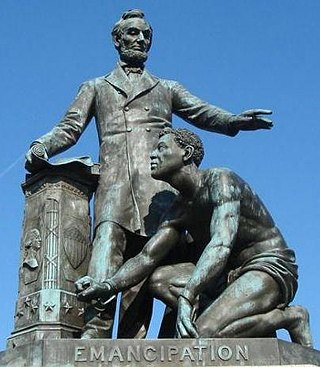

Abraham Lincoln's position on slavery in the United States is one of the most discussed aspects of his life. Lincoln frequently expressed his moral opposition to slavery in public and private. "I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong," he stated. "I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel." However, the question of what to do about it and how to end it, given that it was so firmly embedded in the nation's constitutional framework and in the economy of much of the country, even though concentrated in only the Southern United States, was complex and politically challenging. In addition, there was the unanswered question, which Lincoln had to deal with, of what would become of the four million slaves if liberated: how they would earn a living in a society that had almost always rejected them or looked down on their very presence.

Leonard Williams Levy was an American historian, the Andrew W. Mellon All-Claremont Professor of Humanities and chairman of the Graduate Faculty of History at Claremont Graduate School, California, who specialized in the history of basic American Constitutional freedoms.

Jack M. Balkin is an American legal scholar. He is the Knight Professor of Constitutional Law and the First Amendment at Yale Law School. Balkin is the founder and director of the Yale Information Society Project (ISP), a research center whose mission is "to study the implications of the Internet, telecommunications, and the new information technologies for law and society." He also directs the Knight Law and Media Program and the Abrams Institute for Free Expression at Yale Law School.

David Brown was convicted of sedition because of his criticism of the United States federal government and received the harshest sentence for anyone under the Sedition Act of 1798 for erecting the Dedham Liberty Pole.

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recognised as a human right in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights law by the United Nations. Many countries have constitutional law that protects free speech. Terms like free speech, freedom of speech, and freedom of expression are used interchangeably in political discourse. However, in a legal sense, the freedom of expression includes any activity of seeking, receiving, and imparting information or ideas, regardless of the medium used.

Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age is a non-fiction book about cyberlaw, written by free speech lawyer Mike Godwin. It was first published in 1998 by Times Books. It was republished in 2003 as a revised edition by The MIT Press. Godwin graduated from the University of Texas School of Law in 1990 and was the first staff counsel for the Electronic Frontier Foundation. Written with a first-person perspective, Cyber Rights offers a background in the legal issues and history pertaining to free speech on the Internet. It documents the author's experiences in defending free speech online, and puts forth the thesis that "the remedy for the abuse of free speech is more speech". Godwin emphasizes that decisions made about the expression of ideas on the Internet affect freedom of speech in other media as well, as granted by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

United States Civil Service Commission v. National Association of Letter Carriers, 413 U.S. 548 (1973), is a ruling by the United States Supreme Court which held that the Hatch Act of 1939 does not violate the First Amendment, and its implementing regulations are not unconstitutionally vague and overbroad.

Beyond the First Amendment: The Politics of Free Speech and Pluralism is a book about freedom of speech and the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, written by author Samuel Peter Nelson. It was published by Johns Hopkins University Press in 2005. In it, Nelson discusses how the more general notion of free speech differs from that specifically applied to the First Amendment in American law.

Freedom of Expression® is a book written by Kembrew McLeod about freedom of speech issues involving concepts of intellectual property. The book was first published in 2005 by Doubleday as Freedom of Expression®: Overzealous Copyright Bozos and Other Enemies of Creativity, and in 2007 by University of Minnesota Press as Freedom of Expression®: Resistance and Repression in the Age of Intellectual Property. The paperback edition includes a foreword by Lawrence Lessig. The author recounts a history of the use of counter-cultural artistry, illegal art, and the use of copyrighted works in art as a form of fair use and creative expression. The book encourages the reader to continue such uses in art and other forms of creative expression.

Net.wars is a non-fiction book by journalist Wendy M. Grossman about conflict and controversy among stakeholders on the Internet. It was published by NYU Press in 1997, and was simultaneously made available free as an online version. The book discusses conflicts which arose during the growth of the Internet from 1993 through 1997, labeled by Grossman as "boundary disputes". These disputes deal with issues including privacy, encryption, copyright, censorship, sex, and pornography. The author discusses history of organizations in their attempts to enforce their intellectual property on the Internet, against individuals who attempted to reveal confidential materials asserting it was in the public interest. Grossman frames these disputes with respect to overarching rights of freedom of speech and the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The Best American Magazine Writing 2007 is a non-fiction book published by Columbia University Press, and edited by the American Society of Magazine Editors. It features recognized high-quality journalism pieces from the previous year. The book includes an account by journalist William Langewiesche of Vanity Fair about a controversial United States military operation in Iraq, an investigative journalism article for Rolling Stone by Janet Reitman, a piece published in Esquire by C.J. Chivers about the Beslan school hostage crisis, and an article by Christopher Hitchens about survivors of Agent Orange.

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75 (1947), is a 4-to-3 ruling by the United States Supreme Court which held that the Hatch Act of 1939, as amended in 1940, does not violate the First, Fifth, Ninth, or Tenth amendments to U.S. Constitution.

Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment is a 2007 non-fiction book by journalist Anthony Lewis about freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of thought, and the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The book starts by quoting the First Amendment, which prohibits the U.S. Congress from creating legislation which limits free speech or freedom of the press. Lewis traces the evolution of civil liberties in the U.S. through key historical events. He provides an overview of important free speech case law, including U.S. Supreme Court opinions in Schenck v. United States (1919), Whitney v. California (1927), United States v. Schwimmer (1929), New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), and New York Times Co. v. United States (1971).

The William O. Douglas Prize is given by the Commission on Freedom of Expression of the Speech Communication Association to honor those who contribute to writing about freedom of speech. The Award is named after William O. Douglas, who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 to 1975.

Not in Front of the Children: "Indecency," Censorship, and the Innocence of Youth is a non-fiction book by attorney and civil libertarian, Marjorie Heins about freedom of speech and the relationship between censorship and the "think of the children" argument. The book presents a chronological history of censorship from Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome and the Middle Ages to the present. It discusses notable censored works, including Ulysses by James Joyce, Lady Chatterley's Lover by D. H. Lawrence and the seven dirty words monologue by comedian George Carlin. Heins discusses censorship aimed at youth in the United States through legislation including the Children's Internet Protection Act and the Communications Decency Act.

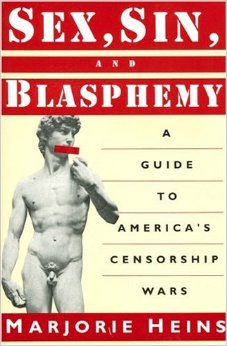

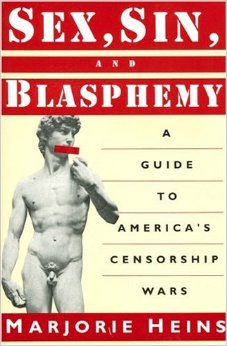

Sex, Sin, and Blasphemy: A Guide to America's Censorship Wars is a non-fiction book by lawyer and civil libertarian Marjorie Heins that is about freedom of speech and the censorship of works of art in the early 1990s by the U.S. government. The book was published in 1993 by The New Press. Heins provides an overview of the history of censorship, including the 1873 Comstock laws, and then moves on to more topical case studies of attempts at suppression of free expression.

A campaign finance reform amendment refers to any proposed amendment to the United States Constitution to authorize greater restrictions on spending related to political speech, and to overturn Supreme Court rulings which have narrowed such laws under the First Amendment. Several amendments have been filed since Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission and the Occupy movement.